Extracted from Straits Times May2013

Will having a basic university degree lead you to the route of a good career?

Our PM Mr Lee Hsien Loong, National Development Minister Khaw Boon Wan, Acting Minister for Social and Family Development Chan Chun Sing and Education Minister Heng Swee Keat - recently spoke on similar themes of how academic qualifications are not a sure ticket to success.

Indeed, Asia "is a bit hung up on that piece of paper", Singapore Management University (SMU) president Arnoud De Meyer tells Insight. A degree helps get a better salary, but it is the experience of learning that is more important in today's age, says Professor De Meyer, who has held top posts at Insead and Cambridge University's Judge Business School.

He also discusses last year's announcement of a 3,000-strong increase in student numbers by 2020, noting that not everybody needs to go to university and there are good jobs that do not require a degree.

· What is your take on the recent debate?Having a good degree helps you to find a better job and a higher salary. It also offers you broader options. If you go for a diploma, usually you're quite specialised.

Even when the PM announced last year that 40 per cent of each cohort will go to university by 2020 (up from 27 per cent now), that still means that 60 per cent will not go to university.

If you look at other advanced countries like the Scandinavian countries or Britain, 40 per cent is in the upper limit.

University degrees offer three things as opposed to a diploma.

First, you get your specialisation, your skills you build up.

Second, it is broad base learning. Students have a lot of flexibility. Most universities now provide the students option to take second major, second degree or electives,etc..

The third, is "learning to learn". What you learn today may be obsolete five years from now. You need to constantly learn new things. That is also what university education provides - a system of learning.

Some other articles typically note that learning how to learn is a process in which we all engage throughout our lives, although often we do not realise that we are, in fact, learning how to learn. Most of the time we concentrate on what we are learning rather than how we are learning it. The process of learning much more explicit by getting you to apply the various ideas and activities to your own current or recent study as a way of increasing your awareness of your own learning. Most learning has to be an active process - and this is particularly true of learning how to learn.

The ministers emphasised the value of work experience and entrepreneurship. Can't these be obtained both in and out of university? Mr Khaw said that it is not about the piece of paper you can hang on your wall but about real experience and the components of your education which is more critical.

That's what universities need to do more in the future - mix conceptual and theoretical learning with practical exposure.

Asia as a whole is a bit hung up on that piece of paper. It's the experience of learning that is more important. A university is both about skills and things like interactions and discussions with each other, the creativity of working day and night on projects, going out, making new friends.

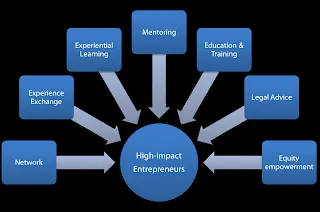

It is also true that we need to become more entrepreneurial, not necessarily setting up a business but in the way we act within the company. Singapore Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship has 55 companies created by our students. They are all small and some of them will fail but you will see that some students have that entrepreneurial attitude.

We have to be realistic. It's not necessary that everybody goes. There are really interesting and good jobs that don't require a university degree and they may be a better fit for people with more practical or artistic aptitudes. We all have different capabilities and should recognise that not everybody will have to go to university.

The second point is, we know from the European experience that if you have too many students going to university, you get graduate unemployment. So underlying the messages from the ministers is, be careful, a degree is no guarantee for a job.

Third, be careful in choosing a line of study. Choose a broad area where there will be demand.

Polytechnic graduates are concerned that in sectors where they compete with university graduates for jobs, starting pay and job progression will differ.

At polytechnics, you get very good people with much more practical skills who can hit the ground running. They start working at 19 for women or 21 for the men, and you could argue that they have four more years of earning money than a university graduate.

University graduates also have to pay their tuition fees. Somehow the market recognises the difference in investments that students have made.

· How has the value of a university degree changed in Singapore? Recruiters ask for more than skills from your studies. They are looking for communication skills and global exposure. They expect us to groom students to be more job- ready.

· How can universities ensure both that their education remains accessible while graduates are employable? By making sure our students are employable.

We have to be realistic. Just because I got a degree in economics today doesn't mean it will be valid 10 years later. That's why our young students nowadays have to think about a broad set of capabilities and skills and to keep improving.

We have to be realistic. Just because I got a degree in economics today doesn't mean it will be valid 10 years later. That's why our young students nowadays have to think about a broad set of capabilities and skills and to keep improving.

I agree with those who believe it to be essential that for example uni lecturers have expertise in their subjects. But such expertise is not limited to certification: if it were, Tony Blair could hardly have taken up a position lecturing in Politics at Harvard when his BA is limited to Jurisprudence. And who would bother listening to Margaret Thatcher droning on about statecraft when her BSc is in Chemistry? And yet many will sit at their feet, because they have qualification way beyond a framed degree.

Thus lecturers should be an expert, but expertise comes in a number of guises. When lecturing ceases to inspire, the learning ceases to engage. When the learning ceases to engage, little or nothing is learned. What unis' and polys' desperately need are outstanding professionals with a sense of vocation: ten of those liberated to draw out students' faculties and intelligences will eclipse a hundred who have been certified and licensed by the institute to impart a centralised curriculum in accordance with government guidelines for the sake of targets and league tables.

Thus lecturers should be an expert, but expertise comes in a number of guises. When lecturing ceases to inspire, the learning ceases to engage. When the learning ceases to engage, little or nothing is learned. What unis' and polys' desperately need are outstanding professionals with a sense of vocation: ten of those liberated to draw out students' faculties and intelligences will eclipse a hundred who have been certified and licensed by the institute to impart a centralised curriculum in accordance with government guidelines for the sake of targets and league tables.