If some of these myths make sense to you, you might very well be on the road to becoming a poor performance manager yourself.

Myth #1: “We are a meritocracy.”

You hear this all the time inside high tech firms, and it’s becoming increasingly common elsewhere, too. The idea is that management only awards promotions and salary increases as the result of proven performance. That’s the theory. But it’s total "BSing".

The idea of a “meritocracy” ignores that many other factors influence who gets what inside a corporation. For example, tall men and pretty women have an inside track that’s purely genetic and has nothing whatsoever to do with their actual contributions.

Similarly, many employees enter a company with pre-existing connections, both through colleagues and family members. A son with minimal talent takes over his father’s job. An executive comes in at the top and pulls a bunch of his cronies in with him. Somebody has an affair with the CFO and then becomes the chief auditor. Deals are cut between drinking buddies. Talent has little or nothing to do with it. Beyond that, the corporate world is full of toadies and lickspittles whose sole ability to survive and thrive is based upon an unerring sense of who in the corporate structure needs periodic sphincter osculations.

Even if those factors were absent from the corporate milieu (which they’re decidedly not), the Peter Principle still remains valid. As anyone who looks at any business carefully can tell you, people could be seened been promoted to their level of incompetence, where they remain in the organization for years and the perception is that these people have been contributing to the growth?

The reason that this belief is so toxic? People who are lucky, connected, or oily use the “meritocracy” belief to justify the fact that they’ve gotten ahead. It makes them feel that they “deserve” their success, and therefore owe nothing to anybody else. Back in the day when belonging to an aristocracy meant automatic advantages, they had a concept called noblesse oblige. Aristocrats knew that they didn’t really deserve their privileges, so they felt obligated to treat the hoi polloi with a modicum of kindness and restraint.

Not so the meritocrats. Once they get ahead, they rapidly become insufferable snobs.

Extracts from David Brooks, Straits Times 14July'12:

Most of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Protestant Establishment sat atop the American power structure. A relatively small network of white Protestant men dominated the universities, the world of finance, the local country clubs and even high government service. Over the past half-century, more diverse and meritocratic elites have replaced the Protestant Establishment. People are more likely to rise on the basis of grades, test scores, effort and performance.

Yet, as these meritocratic elites have taken over institutions, trust in them has plummeted. It's not even clear that the brainy elites are doing a better job of running them than the old boys' network. Would we say that Wall Street is working better now than it did 60 years ago? Or government? The system is more just, but the outcomes are mixed. Meritocracy has not fulfilled its promise. The problem is inherent in the nature of meritocracies. Meritocratic elites may rise on the basis of grades, effort and merit, but, to preserve their status, they become corrupt. They create wildly unequal societies, and then they rig things so that few can climb the ladders behind them. Meritocracy leads to oligarchy.

It's a challenging argument but today's meritocratic elites achieve their rank and status not mainly by being corrupt but mainly by being overly ambitious. They spend enormous amounts of money and time on enrichment. They work much longer hours than people down the income scale. Phenomena like the test-prep industry are just the icing on the cake, giving some upper-middle- class applicants a slight edge over other upper-middle-class applicants. The real advantages are much deeper and more honest.

The corruption that has now crept into the world and the other professions is not endemic to meritocracy but to the specific culture of our meritocracy. The problem is that today's meritocratic elites cannot admit to themselves that they are elites. Everybody thinks they are countercultural rebels, insurgents against the true establishment, which is always somewhere else. This attitude prevails in the Ivy League, in the corporate boardrooms and even at television studios where hosts from Harvard, Stanford and Brown rail against the establishment.

Today's elites are more talented and open but lack a self-conscious leadership ethic code. The language of meritocracy (how to succeed in an honest and sincere truthful way ) has eclipsed the language of morality (how to be virtuous, cunning and shrewd ). Some organization and established firms, for example, now hire on the basis of youth and brains, not experience and character. Most of these organization will eventually face with serious problems and the fact can be traced to this shortcoming.

Myth #2: “I must control employees.”

The idea that the role of management is to control employee behavior is common, but that doesn’t make it right.

We’ve been told for so many years that managers are supposed to be fully “take charge” that any other definition of management seems absurd or naive. All too often, well-meaning managers try to control their way out of problems, control the behavior of the people who work with them, control events that are going to happen whether they like it or not.

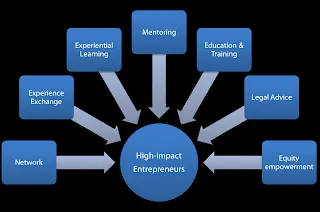

But thinking of management as control misses the entire point (and real power) of management. Ideally, a manager should be a servant, coach and mentor to the people who work inside the group. The goal of the manager is to make everyone else in the group successful, and thereby make the group success. You can’t “control” that outcome. It’s just not possible in some big organization.

The reason this belief is ugly that it leads organization to concentrate power at the top. It causes the proliferation of complicated rules and regulations, the growth of bureaucracies, and the need for expensive reporting mechanisms to pass information up and down the management chain. Thus making the process of decision making tedious and cumbersome and sometimes costing big mistakes due to delay in decision taking.

Even so, the need to control can be very seductive. The illusion that we can bend other people’s hearts and minds and get them to do exactly what we want is a comforting one in a world that’s admittedly chaotic. What’s most dangerous about “control” is that it works-at least for a while, but it eventually creates massive resentment.

The controlling person looks around the conference table one day and finds that he or she is surrounded by "enemies" who would stab the controlling manager in the back, if given half a chance. So the manager comes up with some new way to control or manipulate, while the employees continue to maneuver and posture to avoid the heavy hand of management.

Myth #3: “Our company is like a machine.”

Listen to the way executives talk and business authors write about corporations. A successful corporation is often said to be a “well-run” or even a “well-oiled machine”; it also is said to be a “good system,” one that is “efficient” and “well-designed.” When you hear these descriptions or hundreds of others like them, you’re hearing the belief that employees should be cogs in the corporate machine.

But hold your horses! Machines are, by nature, rigid and stable. Machines never grow; they never change on their own. They only break, because machines are, by definition, comparatively brittle. And isn’t a corporation actually a collection of human beings? Organic creatures who adapt and change with relative ease?

The machine analogy creates other absurdities as well. For instance, machines need to be “greased and run.” Therefore, the whole corporate machine mindset encourages top managers to visualize themselves in the control room of a big machine. This is supposed to make them feel that they’re in control, but ironically it can create a sense of helpless.

A CEO of Xerox once confessed:

I feel like the captain of an aircraft carrier. I turn the wheel and try to point the ship in a new direction, but I have no idea whether or not my orders are being followed.

Why is this belief so toxic? It dehumanizes people. If you think that the everybody is just cog, nobody is essential; anybody can be replaced. What’s important is the machine and (by extension) the people who are running the machine.

That, in turn, creates wretched work environment that cannot and will not reward creative thinking or recognize the value of intellectual differences. People who feel they’re just part of a machine aren’t going to go out of their way to help an organization achieve its goals. In the worst case, they might be tempted to exact some kind of revenge on the company that’s treating its employees like subhumans.

When managers treat employees like cogs, work slows to a crawl. People do the minimum, just enough to keep from getting fired. Then some "smart aleck" manager gets the bright idea to “re-engineer” the machine, thus creating even more misery and even more lousy management.

Myth #4: Business is warfare.”

Many traditional business leaders have a militaristic view of the way the business world works. A glance at the titles of popular business books-Marketing Warfare, Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun, Guerrilla PR-offer ample testimony for this widely held viewpoint. We’re told that we must imitate generals and warlords if we want to be successful managers.

Here’s the problem. If a company’s executives really believe that business is warfare, then that dogma will be reflected in nearly everything that goes on inside the corporation. Strategies that don’t fit the dogma-regardless of their potential for success-will be rejected because they are literally “unthinkable.”

For example, executives who believe that business is a battlefield will almost inevitably assume that victory in business goes to the largest “army” and they’ll build large, complicated departments stuffed full of people and resources. Even when customers would be better served by a smaller, more focused effort, there will be an overwhelming drive to build a massive corporate “army” that’s “strong” and ready to “fight.”

"Military-minded" managers also find it all too easy to become control freaks. Because they see themselves acting as generals, they tell people what to do. They think that good employees should shut up and follow their commander's orders. This behavior destroys initiative as people wait around for top management to make decisions.

And because top management is often the most isolated from the customer, the company loses track of what’s needed in the marketplace. Further, the “business warfare” mentality makes it impossible to put the decision making where it belongs-at the lowest level of the organization.

Military thinking also distances employees from their customers. To the militaristic company, customers are, at best, faceless territory to be “targeted” and “captured” with marketing and sales “campaigns.” This strategy discourages the viewing of customers as living, breathing human beings with opinions, interests, and concerns of their own.

Myth #5: “Employees are like children.”

Lousy managers love complicated rules, procedures, and guidelines that govern nearly every aspect of working life. These rules suggest to employees that they are not trustworthy, lack common sense, and have even less capacity for making important decisions. Employees who “break the rules” or “misbehave” are disciplined… like disobedient children.

It isn’t just manual laborers who are treated this way. White collar employees, too, in many companies are suspected of stealing office supplies, so management locks the supply cabinets, forcing employees to fill out a form to get a pen or printer cartridge.

The absence of trust is implicit. And locking up office supplies forces people to spend valuable work time just accessing the tools they need to do their jobs. This is seen as necessary, however, otherwise employees (children) will be dipping into the corporate cookie jar.

Some Fortune 100 companies whose top management issued company-wide emails complaining about the overuse of paper clips! Try to imagine, in the real world, a conversation between two adults where one suggests that the other should use fewer paper clips. This is pettiness taken to an insane extreme.

This infantilization of the workforce quickly becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. When you treat people like children, they act like children. Disgruntled from the absence of trust and disgusted with management’s patronizing attitude, employees unintentionally become participants in a corporate culture where it’s tempting to waste money, waste time, or even steal company property.

Soon, not only is management treating employees like children, but the employees are acting like children. Managers and employees become trapped in a dysfunctional relationship that, weirdly, starts to resemble a family — a family that badly needs an intervention and years of therapy to become functional again.

TOXIC BELIEF #6: “Fear is an effective motivator.”

Many managers hold the threat of firing or demotion over employees’ heads. The message is clear: “Work hard or you’re outta here!” and recent changes in the economy have made that threat all the more cogent. In the United States alone, tens of millions of workers have lost their jobs as a result of an economic downturn. This resurgence of insecurity in the workplace has reawakened the fear of joblessness in many workers in all fields.

The problem with fear as motivator is that it makes companies less competitive and less adaptable, because it causes workers to become less, rather than more, productive. People become paralyzed and won’t take any action whatsoever lest they be blamed if it goes awry. Or worse, they act out of panic, making things worse.

Organizations where fear rules are truly miserable places. Managers start demanding detailed plans for everything in a vain attempt to guarantee that nothing goes wrong. Decision making to a crawl while everyone seeks to cover his or her behind. Distrust leads to bureaucracies that insist on checking every last detail. Tasks that, in a reasonable organization, could be handled in a few hours, in such an organization might take days, weeks, or months, or never be completed.

Fear also degrades the quality of communications inside an organization. In an effort to deflect potential blame, employees engage in double-talk and “weasel words.” Whenever you see a memorandum that’s a soup of industry buzzwords and half-truths, carefully crafted to spread blame and communicate next to nothing, you can bet that there’s a terrified executive or two cowering nearby.

The result of double-talk is that people in an organization stop valuing truth, even if they can still recognize it. Information that is difficult for the culture to absorb gets buried and avoided. Over time, managers and employees alike lose track of what’s going on in the market because everybody’s afraid to state the facts.

Rather than increasing the level of fear in the organization, effective managers seek to minimize it. They want employees to feel that they are in charge of their destiny-not waiting for the proverbial axe to drop. They want employees to claim ownership for their decisions, not seek to pass or share blame.

Employees who are afraid don’t make good decisions, they don’t take well-considered risks, and they don’t act rationally. Go into almost any conference room in a traditionally run company and you’ll see them. They glance around the room frequently, waiting and worrying, laughing a little too loudly when the boss cracks a feeble joke, agreeing with whatever idea seems popular or politically correct.

Five Common Mistakes with not able to achieve Your Goals?

At work, you’ve probably seen the same phenomenon. Companies establish all kinds of goals–from lofty missions statements to specific growth targets–then often fail to meet most of them.

Why? And what stands in the way of achieving goals? Here are five common mistakes:

1. You underestimate how hard it is to achieve the goal.

Those flabby abs? They can’t be turned into a sexy six pack in six days. Those diet books that promise full body make overs in 30 days? Not going to happen.

In reality, most meaningful goals take a lot of work to realize. If you don’t recognize from the out start that losing ten pounds, or increasing sales 10%, will take considerable time and effort, you will find it all too easy to give up once you get caught up in the day-to-day. You have to forecast the difficulties so that you are mentally prepared to meet the challenges when they inevitably arise.

2. You didn’t “own” your goal.

“I’m just doing this because my boss wants me to” is a goal that is destined for failure. If you’re just implementing a new sales strategy to please the new vice president, not because you believe in its necessity, you’re going to find it impossible to stay on course when you encounter obstacles–or just the daily interruptions.

We’re living in a perfect storm of distractions–email, cell phones, texting, IM, on demand media. It’s way too tempting to tell yourself, “I’m incredibly busy, I’ll get to this tomorrow.” In one survey, people admitted to wasting nearly two hours a day of an 8-hour work day on socializing or goofing off on the internet. Waiting for a “tomorrow” usually means never.

If you want to meet that 10% target, you need to be self-motivated and be committed to achieving it.

3. Your goal wasn’t clear, or measurable.

“Increasing customer satisfaction” is too general. You need to identify the specific, quantifiable goal (ie: improving customer retention by 5 percent), so that you can measure your progress on a regular basis. The on-going monitoring–seeing that retention inched up, or down–will reinforce your strategy and help you stay on track.

Yes, we know that there are people who argue that dieters should never get on a scale–that you can tell if you’re losing weight by how your clothes fit. But how many people actually lose weight that way? And is it really possible to keep focused on that difficult-to-achieve goal, without periodically checking in to see how you’re progressing?

4. You didn’t realize the rewards would be modest.

If you set a goal to increase sales 10%, and so far you’ve inched up sales 2%, you’re probably not going to see the confetti sprinkling down over your head. The sense of satisfaction may be limited. Progress frequently is incremental, and slower than we hope. The key is to remember that fact, so you keep plugging on.

5. You tried to do it alone.

There is a very good reason why so many diet plans encourage dieters to join to support groups. Most of us need a community of supporters who will cheer us on when the going gets tough–and, most importantly, hold us accountable. Just the sheer act of publicly acknowledging your goal can help make you accountable to achieve it.

It takes courage–and humility–to publicly admit that you need to do better. But once you do, having that band of supporters will help you stay disciplined to reach your goal.

How have you achieved a difficult goal? How did you do it?